They come on Tuesdays. Not always the same ones. Sometimes students, cloaked in scholar’s robes with ink-stained sleeves. Sometimes wayward priests, leaning heavy on canes that hide blades. Sometimes no more than servants fetching books for masters who no longer read. They move with a certain kind of purpose, busy but unhurried, eyes scanning spines too quickly, hands pausing just a moment too long on titles that should hold no interest. Some don’t even know why they linger in the alcoves or double back to shelves already passed. But some do.

The library always feels different on Tuesdays, as though it has exhaled some great tension in the night before, after the Ministry inspectors have swept the stacks for unmarked texts that do not belong. That’s when the silence deepens, when the shelves shift ever so slightly, making room. We’ve gotten better at placing them. Better at knowing where the eyes will wander. And so we wait. The curious come on Tuesdays.

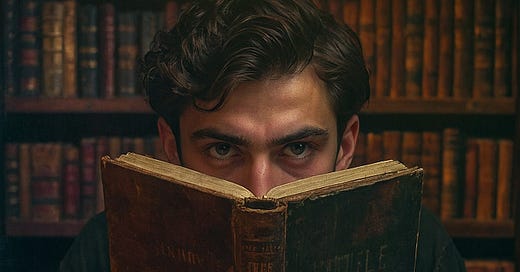

The reader today is different. He hesitates at the archway to the southern alcove, where the dust is thicker and the lamplight less generous. I watch from between the stacks, cloth draped over my shoulders, a feather-duster in my hand. The library sees me as another hired hand, someone meant to sweep quietly between knowledge and memory. They rarely look closer. But I do. I always do.

He steps inside, glancing over his shoulder as if the stones themselves might judge. In the main chamber, the others murmur over their assigned texts, debating scripture and cipher, oblivious. His fingers trail the spines as he walks, tasting names like Petrarch, Hildegard, Alcuin, until they stop on the one we placed. Codex No. 743-B. Philosophia Obscura: Collected Reflections on the Sovereignty of Mind. A false title, wrapped in genuine skin. The catalog number is real, borrowed from a misfiled vellum in the Basel index. The script is aged, the ink cracked, the Ministry of Bookkeeping’s stamp lifted from a burnt ledger during the fire at St. Leontius. Everything about the book belongs here, except the truth it tells.

His hand rests on the spine. I remember the hours that went into crafting that moment. Five of us. Six weeks. Agnes had mixed the ink from burnt walnut and rust scraped from cathedral gates. She wept when it was finished. “This ink will outlive me,” she said, wiping her cheeks with blackened fingers. Jonas copied the text by candlelight, his eyes strained and red, transcribing the final letters of a man executed for speaking aloud the word libertas. Milo, with hands gentle as any priest’s, aged the paper with smoke and cedar. We tore the corners carefully, then stitched the binding with cord pulled from a monk’s robe stolen during morning prayers. And me. I handled placement. The passing of the thing into the world. Each book had to carry the illusion of silence. Not new. Not loud. Just waiting.

The boy’s thumb moves along the edge of the cover. He looks young, no more than twenty, but there’s something patient in his manner, something focused. He lifts the book, slowly, reverently, and for the smallest moment, I forget how to breathe. He opens it, scans the first page, then the second, and keeps reading.

Inside, he finds pages that speak not of kings or saints, but of thought itself. Not a manifesto, no, we knew better than to be that obvious. Instead, poetry. Parables. A letter from a nameless woman to a faceless god, asking why silence must rule the soul. The book whispers of a world beyond this one. A world where the mind is not bound by instruction, but drawn toward wonder. Where liberty is not a threat, but a birthright.

I move a little closer, careful not to draw attention. The clerk at the central desk yawns and returns to her own scribbling, unaware of the heresy unfolding in her library. Light slants through the high windows. Dust spins like frozen time. The boy keeps reading, his eyes fixed, his breath steady. Then, somewhere beyond the stacks, I hear the sound I dread. Boots. Heavy ones. Not the steps of a librarian. Inspectors.

The boy hears it too. His posture stiffens. For a heartbeat I think he’ll slip the book into his satchel and try to flee, but he’s wiser than that. Instead, he closes it carefully, lovingly, and places it back on the shelf. My heart sinks, thinking the moment is lost. But then, as his hand lingers, he slips a torn scrap of parchment between the pages, marking it. Not for himself. For the next.

The inspectors grunt their way past the alcove, their attention caught by the clerk’s stumbling attempt to sound authoritative. I return to my dusting, every muscle pretending calm. The boy is gone, vanished like a whisper between shelves. The book remains.

When the chamber finally empties and dusk begins to settle into the marble, I step to the shelf. The parchment is still there, peeking out like a promise. On one side, a name: Leora, a pen name, of course. On the other, a line from the book: “The mind is not a chalice to be filled, but a candle to be lit.”

I allow myself the smallest smile.

We don’t expect revolution. That’s not what this is. This is survival. This is communion. A thread between kindred minds in a world where silence is enforced like scripture. Each book we plant is a seed. Some are found and burned. Some go unnoticed, gathering dust in forgotten corners. But some are read. Some are remembered. And each time one is opened, the world shifts, just a little. A crack in the great wall of silence.

I tuck the note in and straighten the spine. My part is done… for now. But someone will come. Maybe Leora. Maybe another. And when they read it, they’ll see what we saw: that truth isn’t always loud. Sometimes, it whispers.

And sometimes, that’s enough.